Japan is located a great distance from Europe on the eastern edge of Asia. In the mid-19th century, Japan had no diplomatic relations with other countries, and was a relatively poor, weak, and small country. Its existence was barely even known. However, immediately after it emerged from isolation, whispers began to circulate about the country called Japan—and of a certain region of Japan in particular. Trading in the silk produced in that region—raw silk with a glossy shine—was the objective of foreign merchants visiting Japan. The quality of this raw silk surpassed that produced in other countries. It enchanted and stole the hearts of fashionable Western ladies.

A single thread of raw silk drawn from a cocoon, so small it would fly away if you blew on it. This thin, delicate raw silk raised a small country in the corner of Asia into a world power rivaling the rich and powerful countries of the West. Japan had remained tightly secluded due to its policy of national isolation, but the raw silk from this region enabled Japan to push ahead on the path to modernization.

This fortunate region was made up of the provinces of Joshu and Bushu.

Today, Japan has become a great country—an affluent and peaceful nation. The roots of this lie in the unflagging efforts of the people living in this region at that time. Without the actions of the people in the region, Japan would not have developed as it has today. That is how important the raw silk of Joshu and Bushu was. In this region, the people’s optimistic and high-spirited hopes and dreams were entrusted to a delicate strand of raw silk. From our vantage point in the 21st century, it is a meaningful and valuable experience to reacquaint ourselves with the precious silk heritage still extant in this region, and the passion of the people still living here.

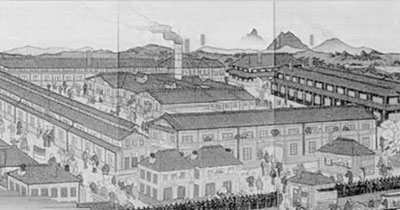

Takasaki is about an hour from Tokyo on the Shinkansen. At Takasaki, transfer to the Joshin Electric Railway and ride for 40 minutes to Tomioka. As you walk through the quiet town, a massive red brick building suddenly comes into view. This is Tomioka Silk Mill. It was at this silk mill—modern even by today’s standards—where the fine raw silk that amazed people all over the world was born.

Japan had just begun a process of Westernization at the time, pursuing policies to build national wealth and military strength, and encourage new industry, so it could participate in international society as a contemporary nation. It emphasized silk exports primarily as a measure for earning foreign currency.

However, high-volume exports were not possible with the hand-reeling methods used at the time. Therefore, Shigenobu Okuma and Hirobumi Ito planned to build a Western-style silk mill. In 1869, a Frenchman, Paul Brunat, was invited to visit the regions of Nagano, Gunma, and Saitama. As a result, it was decided that a modern silk mill would be built in Tomioka, Gunma Prefecture. This area was selected because it had the cocoons and high-quality water required for milling silk, large tracts of land necessary for factory construction, and coal nearby to use as fuel for steam engines.

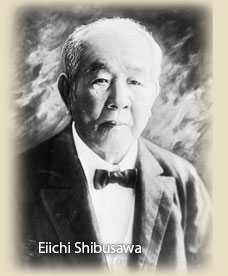

Starting in the Edo period (17th–19th centuries), kimono dealers from all over Japan were already gathering in Fujioka. The area boasted a thriving silk industry and even a silk market. Eiichi Shibusawa was placed in charge of construction and played a central role in establishing the mill. In a nearby area, Naojiro Nirazuka manufactured bricks, which were surprisingly rare at the time.

The government-run Tomioka Silk Mill was opened in 1872. Japan had embarked on its journey toward modernization.

Tomioka Silk Mill was the world’s largest silk mill. When you step into the reeling hall, you find an expansive space without pillars, illuminated by dazzling natural light from glass windows. The space is lined with reeling machines for 300 people. Under the guidance of Paul Brunat, draftsmen, raw silk inspectors, engineers, reeling instructors, doctors, and others were assembled from Yokohama and Brunat’s home country, France, to operate the mill.

Atsutada Odaka was chosen as the first factory manager. He was Eiichi Shibusawa’s cousin and had taught Shibusawa the Analects of Confucius when he was young. In this way, the mill workers mastered their skills every day, under the guidance of foreign experts, and became able to produce high-quality silk in large quantities.

Assiduous efforts to produce high-quality silk extended beyond the premises of the silk mill. The people’s patient temperament, forged by the dry winds unique to this region, was key to the amazing reform of raw silk production.

Sericulture, or rearing silkworms, is a vital part of making high-quality cocoons. Yahei Tajima dedicated his energy to sericulture. He established seiryo-iku, a sericulture method focusing on ventilation. The sericulture room he built in 1863 served as a template for modern silkworm farmers.

The Tajima Yahei Sericulture Farm still stands in Isesaki City and is registered together with Tomioka Silk Mill as a World Heritage Site.

Takayama-sha Sericulture School in Fujioka City (also selected as a World Heritage Site at the same time as Tomioka Silk Mill) was established by Chogoro Takayama as an educational institution for teaching sericulture to a large number of young people who came from around Japan and overseas. He established a method of sericulture called seion-iku balancing ventilation and temperature/humidity control.

Kuzo Kimura, Chogoro’s younger brother, also played a key role in improving sericulture techniques and education. He advocated ippa ondan-iku, a sericulture method combining heating and ventilation, and established the Sericulture Improvement Kyoshin-gumi in 1877. He reorganized this as the Sericulture Improvement Kyoshin-sha in 1884, and built the Kyoshin-sha Sericulture School in 1894. From this school too, young people spread across Japan with newly acquired sericulture skills. Incidentally, Kyoshin-sha has been renamed repeatedly since that time, and received its present name, Saitama Prefectural Kodama Hakuyo High School, in 1995.

Revolutionary ingenuity was also applied to methods of storing silkworm eggs. This innovation can be seen at Arafune Cold Storage, constructed by Seitaro Niwaya in 1905. Here, the storage method utilized cold air blowing from gaps between rocks. This enabled silkworms to be reared multiple times every year rather than just once. This cold storage facility had the largest capacity in Japan, attracting clients from 40 prefectures nationwide, and even from the Korean Peninsula. This valuable legacy is also registered as a World Heritage Site.

The vital role played by women must also not be forgotten. This region is famous for its kakaa denka (lit. “strong-willed wife”), who are even registered as Japan Heritage, and these women were said to be the best workers. The work of women has long been a cornerstone of the silk industry in this region. After the establishment of the silk mill, women made a major contribution working as “factory girls” and weavers of silk products.

It is important to note that many women were engaged in work at the silk mill. Prior to this time, the role of women was perceived as protectors of the home, and women working outside the home was something unthought of. For this reason, there were serious problems when the silk mill was established due to the lack of female candidates to work in the factory. The first factory manager Atsutada Odaka found a solution to this urgent problem. He hired his daughter, Yu, as the very first “factory girl.” Women seized the opportunity, and gathered from around the country. At first, many were daughters of former samurai families from rural areas—hailing from 32 prefectures nationwide. Working conditions were surprisingly good, even by today’s standards. The average working day was 7 hours and 45 minutes. There was no work on Sundays, and the government bore the cost of food and medical expenses. The premises were equipped with dormitories and a medical clinic. Women who finished their training were encouraged by the government to return to their hometowns and become leaders at local silk mills. Through these women, the latest techniques learned at Tomioka spread throughout Japan. The speed with which women were able to advance in society was indeed quite remarkable. One can get a feeling for the vitality of the “factory girls” at the time by reading the memoir Tomioka Diary by Ei Wada.

Tomioka Silk Mill was the focus of activity for a large number of people in this era. The new mill also brought about changes in the surrounding areas. River transportation on the Tone-gawa River developed to transport large quantities of silk. Railways were another key infrastructural element. One after another, steep mountains were cut away to open the Usui Line, Takasaki Line, Ryomo Line, and Kozuke Railway (present-day Joshin Electric Railway). The Takasaki Line in particular played a critical role as a rail link between Joshu and Yokohama. In recent years, this route has been used as the Shonan–Shinjuku Line. The development of water transportation and railroads had a major impact on Japan’s silk industry.

The nations of the West had achieved prominence over a long period of time, but Japan—despite being a country of wood and paper with no particular strengths or natural resources—became a world power in an amazingly short period of time. This surprising development was not achieved by politicians or soldiers. The force behind the change was the common people—industrialists, scientists, businessmen, and women—who had previously been barred from participating in the working world. In other words, the people who led Japan to become a modern state through the Meiji Restoration were the commoners who had been a quiet presence during the Edo period. Through these people freely demonstrating their talents, Japan transformed into a world power that amazed those in Western countries. The driving force behind this was the high-quality silk industry scattered throughout the country and centered on Tomioka Silk Mill.

A government-run silk mill was established in Tomioka, and the raw silk industry developed through the unflagging efforts and passion of local people into an industry that swept the world.

A harbinger of this was the Vienna World’s Fair held in 1873. There, the raw silk of Tomioka received high acclaim. Overnight, the name “Tomioka Silk” spread throughout the countries of Europe. At the time, Eiichi Shibusawa had been given the mandate of compiling a book on sericulture and was working to expand the reach of Japanese raw silk to the world. This book was entitled Sanso Shusei (“Collection of Knowledge on Silkworms and Mulberries”). Later, at the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, Japanese silk again received tremendous praise, and at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, raw silk made by Usui-sha was honored with a prize. A Japanese silk craze swept the globe. Marco Polo, a traveler on the continental Silk Road, had reported rumors of Japan as “Zipangu, the land of gold,” but it had now come to be known as “Japan, the land of silk.”

Japan’s history of overseas trade in raw silk dates back to 1859. In the same year, the Port of Yokohama was opened to overseas trade due to the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan, and companies such as the British Jardine Matheson & Co. and Dent & Co., and the American Wall & Co., began trading. In no time, raw silk from Japan became the top export item that traders from the West battled to purchase. This was accompanied by a massive influx into Yokohama of determined people from across Japan wishing to trade. Starting with Jubee Nakaiya, known as the founder of the raw silk trade, powerful wholesalers from Joshu and Bushu opened one wholesale shop after another. Merchants including Sobee Mogi and Zenzaburo Hara also contributed greatly to the raw silk business.

Merchants called zaikata ninushi began to appear. They purchased silk from their home regions and brought it to Yokohama to sell. As brokers, they reaped huge profits. A notable zaikata ninushi, Zentaro Shimomura, had started trading overseas in 1863 as a silk cocoon merchant in his hometown, Maebashi. His quick grasp of market prices for silk in Yokohama enabled him to accumulate great wealth, and contribute to the development of Maebashi. He also exported silkworm eggs overseas in 1876 and poured his energy into maintaining the quality of raw silk. It was largely due to the efforts of these merchants that Japanese raw silk was exported overseas.

That was not all. Some of these merchants wanted to sell raw silk overseas directly without it passing through the hands of foreign brokers.

One such person was Kenso Hayami, general manager of Tomioka Silk Mill. He established Yokohama Doshin-Kaisha in March 1880 and focused his energy on direct exports of raw silk.

The efforts of the Hoshino-Arai brothers resulted in a major expansion of direct silk exports. In 1874, Chotaro Hoshino, originally from Gunma Prefecture, established the Mizunuma Silk Mill, a Western-style mechanized silk mill, and shipped a large volume of raw silk. In 1876, he sent his brother, Ryoichiro Arai, only 20 years old at the time, to New York in the United States, where they realized Japan’s first direct raw silk exports.

The beginning of the Meiji period was a time when the Japanese were regarded as a race of people from an isolated country, and as such, were often not dealt with fairly. It was doubtless very difficult at the time for a young Japanese man with no connections to try to conduct business. However, the brothers had strong convictions and succeeded in carrying out their original intention.

There was a man who appreciated the passion of the two brothers and provided tremendous support. That man was Motohiko Katori, a councilor to the Meiji Government. He was also a younger brother-in-law of Shoin Yoshida, an imperial loyalist at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. Katori was stationed at Maebashi as the first prefectural governor of Gunma, and contributed greatly to the continuation and development of Tomioka Silk Mill. It is also of note that Ryoichiro Arai, was the grandfather of Haru Reischauer, wife of Edwin Reischauer, former US ambassador to Japan.

The raw silk Arai exported to the United States at the time was used for small articles, such as ribbons and handkerchiefs for women. Tomioka Silk stole the hearts of American women. Later, Tomioka Silk stockings in particular had a great impact—enough to alter the course of women’s fashion.

Thanks to the activities of such people, the volume of raw silk exports increased dramatically and brought a huge financial windfall to Japan.

Furthermore, the destination for Japanese exports made a major shift from European countries to the United States. At the beginning of the Meiji period, the United Kingdom accounted for 50 percent of Japanese raw silk exports, but by 1885, 58 percent of Japanese exports were headed for the United States, eventually reaching 70 percent by 1907. By 1909, the volume of Japanese exports of raw silk accounted for 80 percent of the world market share.

One must not overlook that behind this success were the high quality of the raw silk and technological innovation of the machinery. One such example was the Minorikawa multiple-spool silk-reeling machine. Product made with this machine was highly acclaimed as Minorikawa Silk.

After the war, this technological innovation resulted in the automatic silk-reeling machine, an advance closely connected to the emergence of modern Japanese companies representing Japan in areas such as the automobile industry.

There are other key individuals who must not be forgotten. Today, there is an expansive Japanese garden called Sankeien in Honmoku, Yokohama. This exquisite garden was landscaped by Sankei Hara (a.k.a. Tomitaro Hara). Sankei, who was born in Gifu, took over Kameya, one of the top two raw silk export merchants in Yokohama established by Zenzaburo Hara. He was also involved in the management of Tomioka Silk Mill. He used his considerable business acumen to implement modern business management operations. Although he accumulated immense wealth, rather than monopolizing it, he contributed greatly to society, in areas such as supporting the young artists of the time.

In this way, raw silk produced at Tomioka became number one in the world in terms of production and export volume. Finally, the country had joined the ranks of the world’s leading nations as “Japan, the land of silk.”

Tomioka Silk spread throughout the world over the span of a few short decades. The massive influx of foreign currency from exports fueled Japan’s modernization to the extent that it rivaled the great world powers. Tomioka Silk Mill, a wellspring of this wealth, was privatized in 1893, with Takayasu Mitsui winning the bid. Then, in 1902, the mill was acquired by Hara GMK and management was taken over by Tomitaro Hara, the builder of Sankeien. Hara established representative offices in the United States, Russia, and Europe and actively expanded exports of raw silk. Later, Katakura Seishi Boseki, which had been expanding silk-milling operations in Suwa in the Shinshu region, took over management of Tomioka Silk Mill in 1939.

After the war, despite the decreased demand for silk products due to the proliferation of products such as nylon, Tomioka Silk Mill continued to produce high-quality raw silk. Finally in 1987, its role fulfilled, Tomioka Silk Mill closed its doors.

The curtain fell on the last chapter of the history of the silk industry that had supported modern Japan.

Fortunately, even after closing, Tomioka Silk Mill has been preserved as is. Today, still, people can catch a glimpse of how things were in the past. Tomioka Silk Mill is once again in the limelight on the world stage.

The 38th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee was held in Doha, Qatar, on June 21, 2014. “Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Sites” were deliberated upon and of the 21 countries including Japan represented, 18 expressed support for registration. There were no objections. That same day at 10:55 a.m. (4:55 p.m. Japan time), the collective registration of these sites as a World Heritage Site was formally decided. The single-minded efforts of residents of a rural part of Japan, a small country in the Far East, and the impact of those efforts in developing modern Japan were recognized and acclaimed. The people filling the venue must surely have been moved to be in attendance for such a historic moment.

A great accomplishment buried in the obscurity of history. Looking back at the history of modern Japan, there tends to be a bias toward the role played by heavy machinery, but we should never forget that underlying it all was raw silk.

Sericulture techniques were developed over a long period of time. Our forebears were focused solely on producing the highest quality raw silk. When Japan awoke from its long isolationist slumber, it had no major industries apart from rice and silk. Compared to the powerhouses of the Western world, Japan at the time was a poor, weak country that would fly away if you blew on it.

In dealing with people from foreign countries, the people at the time remained undaunted. They worked tenaciously and hard, with the courtesy characteristic of Japanese culture. They continued hand-reeling thin, delicate strands of raw silk—the only thing they could hold up to the world with pride. The pioneers of the time at Tomioka, and in the Joshu and Bushu regions, kept working steadily in a Zen-like state . The wealth then obtained here helped fund the modernization of Japan.

The feats of these pioneers dot the landscape of this region. In addition to Gunma’s silk legacy already collectively recognized as a World Heritage Site—Tomioka Silk Mill, Takayama-sha Sericulture School, Tajima Yahei Sericulture Farm, and Arafune Cold Storage—you can also experience many other sites with precious heritage in the surrounding area.

The people of Japan attained development rivaling the West, and then accomplished the amazing feat of rebuilding from the devastation of defeat after the war seven decades ago. The sources of this precious spirit were present in the pioneers living in Joshu and Bushu. The same mindset lives on in the flesh and blood of the people who live in this area.

Walking once again through this region, following a single thin and delicate strand of silk, we can feel for ourselves the wonderful power of the Japanese people that was once forgotten.

People living today are sure to find a message from the past—a precious message worth passing on to their own children.