Several men from Fukaya played a major role in construction of Tomioka Silk Mill.

People with an intriguing connection joined hands to lay the foundation.

Through this story, one can see their dream and grit in building a new country.

Tomioka Silk Mill, the first large-scale government-run silk mill in Japan, was the starting point for the industrial revolution in Japan and Asia. It played a central role in the modernization and internationalization of Japan from the Meiji period onward. The extant structures of the mill are unparalleled in the world both as buildings representing the transfer of modern Western European technology and as the oldest and largest factory constructed with home-grown capital outside of the Western European region.

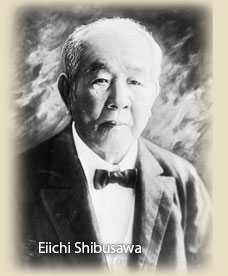

Tomioka Silk Mill is a symbolic presence on the Jobu Silk Road. Three men from Fukaya were key figures in its establishment: Eiichi Shibusawa, Atsutada Odaka, and Naojiro Nirazuka. Shibusawa was a member of the government and led the effort as chief of setting up operations for the mill. Odaka was involved in construction of the silk mill and became the first factory manager. Nirazuka was responsible for procuring construction materials. These three men shared the same hometown, and an intriguing connection of destiny.

As a key figure in the Meiji Government, Eiichi Shibusawa worked together with Hirobumi Ito to establish Tomioka Silk Mill. Shibusawa was the son of a wealthy farmer engaged in sericulture and making balls of dried indigo for indigo dyeing, so he was knowledgeable about sericulture. Also, from the end of the Tokugawa shogunate to the beginning of the Meiji period, he travelled as an observer to Europe and disseminated information about goings on in the West.

Shibusawa recommended that Atsutada Odaka be put in charge of building the silk mill. In fact, Shibusawa and Odaka were cousins (Odaka was older by 10 years) and when he was seven years old, Shibusawa had been a student at a private academy operated by Odaka in the house where he was born. It was under the tutelage of Odaka that Shibusawa studied the Analects of Confucius, his spiritual foundation.

In later years, Shibusawa was involved in the establishment of as many as 500 businesses stemming from his concern for public welfare and his philosophy of “the unity of morality and economics.” He was also instrumental in many public projects and promoting international goodwill. It is said that the spirit of the Analects—sincerity and consideration—was always at the heart of his energetic activities. This conjures up the image of the young Eiichi reciting the Analects while seated in front of Odaka, who was like an elder brother, in the small “Aburaya” academy (the shop name of the house of Odaka’s birth).

Atsutada Odaka was born into a family who served as myoshu, or village headmen. He excelled at academics from a young age, and opened an academy in the house where he was born, built by his great grandfather in the late Edo period.

In 1869, Odaka protested changes made by local authorities regarding water supply for agricultural purposes and resolved the issue by petitioning the government. This action brought him to the attention of high-ranking government officials and he was subsequently recruited to serve the new government.

Odaka was involved in establishing Tomioka Silk Mill from the stage of site selection. He took great pains to procure the cedar posts essential for the unique “wood frame, brick construction” structure and placed Naojiro Nirazuka in charge of making bricks. Naojiro was seven years older than Odaka, but he had lived with the Odaka family until he was seven. He contracted Washigoro Hotta and his son Chiyokichi, plaster craftsmen from the same hometown, to modify shikkui plaster for use as mortar for joining bricks.

When the silk mill started operation, Odaka became the first factory manager. Guided by the principle “a sincere man has the insight of the gods,” he devoted himself diligently to management. In addition to maintaining discipline at the silk mill, he was concerned with the training of the “factory girls,” undertaking to improve not only their skills, but also their general education.

Naojiro Nirazuka was the son of an oil press worker working for the Odaka family and a live-in domestic servant at the Odaka home, and he lived with the Odaka family until the age of seven. Later, he married the daughter of a Hikone samurai family who became an adopted daughter of the Odaka family. During the uproar regarding changes to water supply for agricultural purposes, he worked with Atsutada Odaka to resolve the issue.

Odaka, who was in charge of the construction of Tomioka Silk Mill, turned organizing the procurement of building materials over to Naojiro. Naojiro moved to Tomioka to assume his duties, leaving behind his family. Of all the building materials, bricks were particularly problematic. Naojiro obtained information about the characteristics of bricks from a French technician and searched for clay of suitable quality. He assembled a group of local roof tile craftsmen and began making bricks. Through trial and error, he was able to make the bricks that have withstood wind and snow, and support the building to this day. When the silk mill started operations, Naojiro was put in charge of the kitchen and dining hall.

Later, in an expression of gratitude for the success of Tomioka Silk Mill, Naojiro dedicated large wooden votive tablets depicting the silk mill at Sasamori Inari-jinja Shrine in Kanra, and Eimei Inari-jinja Shrine in Fukaya City. In later years, when Eiichi Shibusawa was involved with establishing Nihon Renga Seizo KK, Naojiro worked hard to explain the project to local residents.

Another key figure in the story of Tomioka Silk Mill is Atsutada Odaka’s eldest daughter, Yu, also from Fukaya. Yu took the initiative and joined the mill in response to a recruitment call for trainee women workers. Due to a rumor circulating at the time, there were initially almost no applicants for this position. The rumor was that foreigners drained people’s blood, and it arose from a misunderstanding that the wine drunk by the French was actually human blood. More than just a false rumor, this was a serious mental image held by people who had just emerged from an era of strong anti-foreign sentiment.

The following is an excerpt from Atsutada Odaka’s biography Rankou'ou: “They say the foreigners in your employ are actually demons using sorcery, and you’re bringing young girls into the factories on their orders. They immediately drain the blood from these unfortunate factory girls and kill them. That’s why no one is applying to work at the mill.”

The bold action of Yu, known as the very first “factory girl,” dispelled this canard. Yu’s decision inspired girls from her hometown and five girls, including Kura Matsumura and even Kura’s grandmother, Washi, went to work at the factory.

The landscape of Fukaya is dotted with other important heritage sites essential to the story of the Jobu Silk Road.

“Nakanchi,” the former residence of Eiichi Shibusawa is still standing, as are the house where Atsutada Odaka was born and the brick-making facilities of Nihon Renga Seizo KK.

In 1886, the Meiji Government made plans to build Western-style brick buildings in the government office precinct of the Hibiya district of Tokyo, and requested that Eiichi Shibusawa establish a brick-making factory. Shibusawa selected Joshikimen in Fukaya as the factory site due to its favorable conditions: previous manufacturing of roof tiles, a high-quality clay layer, and convenient river transport via the Tone-gawa River. An office and Hoffman kilns were constructed in 1888, and operations commenced. Bricks made by Nihon Renga were used in the construction of notable structures such as Tokyo Station, the Bank of Japan building, and the Akasaka Palace. The Hoffman kilns were used until 1968, and the factory itself was operational until 2006. Currently, the former office (now a history museum) and Hoffman Kiln No. 6 are open to the public.