What is the appeal of human beings, the power of people who accomplish things?

Diverse characters wove the world of the Jobu Silk Road.

We delve into their thoughts and highlight the power of people.

Who stands at the beginning of the Jobu Silk Road?

From the standpoint of chronology and importance, it is surely Jubee Nakaiya.

Jubee Nakaiya’s appearance in Yokohama coincided with the opening of the Port of Yokohama. He was a pioneer and key player in the silk trade.

Jubee was born in Nakai, Joshu Province (Mihara, Tsumagoi-mura, Gunma Prefecture) in 1820. He went to Edo (present-day Tokyo) during the turbulent times of the late Tokugawa shogunate, where he was involved with the imperial loyalists. He was 40 years old when he arrived in Yokohama. An excerpt from Yokohama Kaiko 50 Nenshi (“Fifty-Year History of the Opening of the Port of Yokohama”) published in 1909, states that Jubee “was quick to see an opportunity and acted before other merchants.” He built a grandiose store named Akagane Goten and began trading in raw silk for export. According to archives of correspondence from 1859, at the time of the opening of the Port of Yokohama, Jubee’s export volume of raw silk was 10.8–11.4 tons—far greater than his closest competitor at 3.0–3.6 tons. Jubee purchased raw silk primarily from Joshu and actively marketed it to foreign trading houses. In both name and reality, he was the pioneer of the raw silk trade and was spectacularly active for about two years in the early period of the port before he suddenly disappeared. Although there are many theories regarding his disappearance, it is still shrouded in mystery.

The house where he was born in Tsumagoi is now a traditional Japanese restaurant called “Nakaiya.” Nearby is a grave where it is said some of Jubee’s hair is buried.

“The general idea behind sericulture is not unlike cultivating oneself” says an excerpt from Yosan-Shinron (“A New Theory of Sericulture”). Yahei Tajima advocated a method of breeding silkworms and raising silkworm eggs in accordance with the principles of nature. He modified his sericulture room and devised a yagura tower structure for ventilation.

Yahei Tajima was born in Shimamura (Sakaishimamura, Isesaki City), in the silkworm egg producing area on the border of Joshu and Bushu Provinces in 1822. He inherited the virtuous qualities of his scholarly father, Yahee, with whom he traveled to silkworm egg producing areas in Tohoku and elsewhere. His books, Yosan-Shinron (1872) and Yosan-Shinron II (1879) were highly acclaimed for their basis in empirical research and influenced many silkworm egg farmers and sericulture farmers.

In 1872, Yahei participated in establishing Shimamura Kangyo Kaisha, with a group of like-minded associates, for the purpose of producing and selling high-quality silkworm eggs. He established the company on the recommendation of Eiichi Shibusawa, who had connections to the Tajima family. In 1879, he went overseas with silkworm eggs (silkworm-egg papers) accompanied by two employees, and engaged in direct exports to Italy.

The silkworm egg exporting trend gradually declined and Shimamura Kangyo Kaisha was dissolved in the mid-1880s. However, the steadfast Yahei continued in the silkworm egg business his entire life. He was also a cultured man skilled in writing poetry and painting.

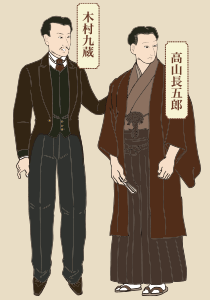

The brothers Chogoro Takayama and Kuzo Kimura are symbolic of the connection between “Jo” (Joshu) and “Bu” (Bushu).

The brothers were born in Takayama, Joshu Province (Takayama, Fujioka City, Gunma Prefecture) to a sericulture family. The family estate was inherited by Chogoro, and Kuzo was adopted by the Kimura family of the Shinshuku in Bushu Province (Shinshuku, Kamikawa-machi, Saitama Prefecture). Both boys were interested in sericulture from childhood. When they grew up, Chogoro developed the seion-iku sericulture method balancing ventilation with temperature management, and Kuzo developed the ippa ondan-iku sericulture method regulating temperature and humidity in sericulture rooms using charcoal fire and ventilation. Born in 1830, Chogoro was 15 years Kuzo’s elder, but they were as close as brothers could be and healthy rivals, refining their sericulture methods while sharing information.

Both brothers founded their own sericulture associations—Chogoro founded Takayama-sha, and Kuzo founded Kyoshin-sha. These associations flourished and became major centers for sericulture education. Takayama-sha Sericulture School was a mecca for sericulture in Japan, and branch schools established primarily within Gunma Prefecture attracted students from all over Japan and even China. Kyoshin-sha established branches (i.e. training facilities) throughout Japan. Around the 1910s, it boasted more than 30 branches nationwide with more than 30,000 members on its books. Kyoshin-sha Sericulture School later became Saitama Kodama Agricultural High School, and is now Kodama Hakuyo High School. Its legacy of sericulture continues today in its biological resources course.

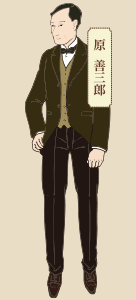

Between 1902 and 1939, Tomioka Silk Mill was managed by Hara GMK with roots in Saitama Prefecture.

Zenzaburo Hara, patriarch of the Hara Zaibatsu business conglomerate, was born in Wataruse in Bushu Province (Wataruse, Kamikawa-machi, Saitama Prefecture) in 1827. In 1862 in Yokohama, he established Kameya, a raw silk export business, and accumulated a fortune. He constructed silk mills in his hometown, Kamikawa, and in Shimonita in Gunma Prefecture, which later became the foundation for Hara GMK. The site of his immense villa is now Tenjinyama Garden in Kamikawa. Tomitaro Hara (born in 1868) was adopted into the Hara family and became Zenzaburo’s successor. He restructured the businesses into Hara GMK and entered the silk manufacturing business in earnest. In addition to acquiring Tomioka Silk Mill from the Mitsui family, he bought three additional silk mills where he implemented a modern style of business management.

The Hara Silk Mill (later the Hara Wataruse Silk Mill) in Kamikawa was operational until the early Showa period, but in 1940 it became Japan Mica’s factory for manufacturing mica for insulators. Even today, there are extant cocoon storehouses, a silk-reeling factory, and water storage tanks on the premises of Japan Mica Industrial, providing a glimpse into its days as a silk mill.

Kenso Hayami is remembered as the man who made the first mechanized silk mill in Japan, and as a figure who improved management of Tomioka Silk Mill and ensured its survival through to privatization.

Kenso Hayami was born in Kawagoe in 1839. Through the forced relocation of the daimyo (feudal lord) from the Kawagoe Domain to the Maebashi Domain, he became a retainer of the Maebashi Domain. On orders of the daimyo, he opened a business in Yokohama wholesaling raw silk for export. He learned about silk-milling machine technology from Casper Müller of Switzerland and together with Yuzo Fukazawa and others established the domain-run Maebashi Silk Mill, the first mechanized silk mill in Japan in 1870.

Hayami was called upon to become an official of the Ministry of Home Affairs, and because he was judged to have experience and management skills relating to mechanized silk milling, he was appointed the third factory manager of Tomioka Silk Mill in 1879. The following year, he participated in the establishment of Yokohama Doshin-Kaisha, a concern engaged in direct export of raw silk, and resigned from his post at Tomioka Silk Mill. He was reappointed as the fifth-serving factory manager in 1885 and remained manager for eight years until sale of the silk mill to the Mitsui family in 1893. While Hayami was moving forward with silk mill reorganization, he increased exports to the United States through Yokohama Doshin-Kaisha and enhanced the reputation of Japanese raw silk.

In managing the silk mill, he improved the living and learning environment of the female workers in keeping with his philosophy that “the work of silk milling is spiritual work.”

Privatization of Tomioka Silk Mill was an issue, and some said the mill should be shuttered because its role as a government-run model training factory was finished, but Hayami dismissed that idea and insisted on keeping the mill going as a flagship factory for mechanized silk milling, and even after transfer to the Mitsui family Tomioka Silk Mill continued to survive.

Ryoichiro Arai was born to the Hoshino family in Mizunuma, Joshu Province (Kurohone-cho, Kiryu City, Gunma Prefecture) in 1855. He was adopted by the Arai family, raw silk merchants in Kiryu. After attending Tokyo Kaisei School (predecessor of the University of Tokyo) and Tokyo Shoho Koshujo (Commercial Training School, predecessor of Hitotsubashi University), he went to the United States in 1876 to pioneer the raw silk market and initiate direct exports. He succeeded in direct sales of raw silk from the Mizunuma Silk Mill operated by his elder brother, Chotaro Hoshino. It is said that this was the first direct export of raw silk that did not pass through the hands of foreign merchants at the foreign settlements. The Mizunuma Silk Mill was the first privately-run mechanized silk mill in Gunma, and had been opened based on mechanized silk-reeling technology Chotaro Hoshino learned from Kenso Hayami. Later in life, Ryoichiro Arai lived in the United States and promoted raw silk trade and friendly relations between the United States and Japan as a pioneer international businessman.

A well-known episode relating to Ryoichiro is that when he was leaving for the United States, Kotobuki, the younger sister of Shoin Yoshida and wife of Motohiko Katori, presented him with a short sword that was a memento from Shoin. The sword passed to Ryoichiro’s descendants living in California and was entrusted to Maebashi City by his descendants in 2016.

Ryoichiro died at his home in Connecticut in 1939 at the age of 84. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York. In honor of his passing the New York Board of Trade held a moment of silence. In his obituary in the New York Times, he was hailed as the founder of the Japanese-American raw silk trade.

The site of the house where Ryoichiro was born (Kurohone-cho, Kiryu City) now serves as a summer camp grounds for Nishimachi International School (headquartered in Nishi-Azabu, Minato-ku, Tokyo, established by Ryoichiro’s grandchild, Taneko Matsukata)