Female workers known as “factory girls” from all over Japan gathered at Tomioka Silk Mill and dedicated themselves to study.

Taking pride in their jobs and acquiring the necessary skills made them pioneers for women in the workforce.

Their footsteps also played a role in connecting the Jobu Silk Road.

To lay the foundation for encouraging new industry, the Meiji Government focused on the silk-milling industry as a means of obtaining foreign currency, and in February 1870 decided to establish a Western-style mechanized silk mill. At this time, policies were established to adopt foreign silk-milling machines, invite foreign experts, and recruit “factory girls” from around Japan to acquire new skills. Additionally, an announcement issued in May 1872, prior to the establishment of Tomioka Silk Mill, stated “The purpose is for these women to learn how to mill silk, so that they can disseminate the techniques throughout Japan.”

At the time of its establishment, Tomioka Silk Mill was positioned as a model training factory, for recruiting female workers from around the country and teaching them mechanized silk-milling techniques, so they could become leaders and disseminate the new technology nationwide.

The modernization of Japan was entrusted to the factory girls reeling silk at Tomioka Silk Mill with “dexterous and delicate fingers” (Georges Bousquet, in Le Japon de nos jours et les echelles de l’Extrême Orient).

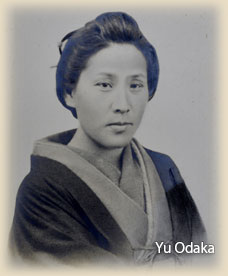

Due to groundless rumors based on aversion to foreigners, recruitment of “factory girls” for Tomioka Silk Mill did not proceed as anticipated. However, the daughter Yu of the first factory manager Atsutada Odaka and others joined the factory of their own initiative in July 1872, and operations were able to commence at the silk mill on October 4, 1872. By April 1873, the total number of female workers had reached 556.

The “factory girls” came from all walks of life including noble families, samurai families, and commoners, but between April 1873 and March 1888 more than 30% of the women who passed through Tomioka Silk Mill were from samurai families (according to Tomioka-shishi [“Tomioka City History”] and other sources), a greater number than their representation within the population. From the lyrics of a song popular in Tomioka at the time, one can get a sense of the high regard in which the “factory girls”were held as working women: “Hair in a bun with a flowered hairpin, Everyone dressed in purple hakama, Clothes tied back with crepe tasuki,

The wonderful figure of a girl reeling silk.”

The initial purpose of establishing Tomioka Silk Mill was to foster female workers with cutting-edge skills. Young women from all around Japan joined the mill with a sense of pride. Ei Wada (née Yokota) wrote a memoir entitled Tomioka Diary that sheds light on the life of “factory girls” during this time.

In the early stages of Tomioka Silk Mill, many of the female workers joining the mill were from northern Saitama Prefecture. Those record books are still extant. Northern Saitama Prefecture was geographically close to Tomioka Silk Mill, had an active sericulture industry, and was the location of Fukaya, the hometown of Eiichi Shibusawa and Atsutada Odaka, two key figures in the establishment of Tomioka Silk Mill. The fact that Yu Odaka took the lead, bringing in “factory girls” from the nearby region, also had a considerable effect.

On the Jobu Silk Road, we can still trace the footsteps of the “factory girls” who joined Tomioka Silk Mill from places such as Fukaya, Kumagaya, and Honjo (according to records many came from the towns of Ogawa and Ogano), learned mechanized silk-milling techniques, and returned to their hometowns. Others joining at the same time as Yu Odaka—such as Washi Matsumura of Fukaya, and Teru Aoki and Masu Maeda from Ogawa—were older and took care of the younger “factory girls.” Masu Maeda herself raised money for the “factory girls” who passed away to pay for Buddhist prayers to be said on their behalf in perpetuity.

Although these women joined Tomioka Silk Mill from all around Japan, unfortunately the only records pertaining to the “factory girls” that remain from the early period are for those from Saitama Prefecture and Nagano Prefecture. These give us a partial grasp of the origins of the Jobu Silk Road.

Jobs at Tomioka Silk Mill were divided—based on experience in the mill and skills—into cocoon grading, silk reeling, re-reeling, inspecting, and other tasks. Cocoon grading involved sorting the raw material cocoons by quality. Re-reeling was the process of reeling silk from smaller silk frames onto larger frames. As evident from the song lyrics “The wonderful figure of a girl reeling silk,” the star of the show was silk reeling (the task of sitting in front of the silk-milling machine, taking cocoon filaments from the basin, and winding the filaments onto frames of the machine). The ultimate goal of the “factory girls” was to learn this silk-reeling technique.

Generally speaking, the girls at the mill were promoted in stages through the ranks: cocoon grading, re-reeling, and silk reeling. They were also divided into grades according to their degree of proficiency in silk reeling. When the mill opened in October 1872, there were four grades of “factory girl”: third through first grade and non-graded. However, this system was revised in April 1874 to a system with eight grades—exceptional non-graded, and seventh through first grade. The women refined their skills and competed for proficiency as they worked toward the goal of rising through the ranks to become a “first-grade factory girl” before returning home.

Tomioka Silk Mill was the start of Japan as a modern industrial nation, and the departure point for the modern factory system with a structured labor environment.

The premises incorporated dormitories, a dining hall, and medical facilities. All the “factory girls” it was a dormitory lifestyle, with everyone living onsite. Room, board, and medical expenses were all covered, and uniforms were provided.

Tomioka Silk Mill is said to have been the first in Japan to introduce a week-based system with a six-day workweek and each Sunday off. In the beginning, rules stipulated about eight hours of work each day, with two 10-day vacations during the summer and New Year’s holidays. According to Seishijo Kenbun Zasshi (“Silk Mill Information Magazine”) published in 1875, working hours were carefully adjusted to suit the season. For example, there were four hours off during the day in the hot and humid summer season.

Opportunities to use free time for education were also provided. A school for the women workers was set up by 1878, and educational opportunities for them continued even in the period after the Mitsui family took private ownership.

The “factory girls” who mastered silk-milling skills at Tomioka Silk Mill returned to their hometowns and disseminated new techniques to silk mills set up all over Japan. Ei Wada, author of Tomioka Diary, returned to her hometown in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture in 1874 to become a leader at the privately-run Nishijo Silk Mill (later Rokko-sha). Women from Tomioka Silk Mill were also invited to teach at a Tomioka-style silk mill established by the Hokkaido Development Commission, as well as a mechanized silk mill still extant in Sakata City in Yamagata Prefecture (presently operated by Matsuoka Co., Ltd.), and other facilities.

“Techniques were reliably transmitted via the hands of ‘factory girls’ after they returned home from Tomioka, and the silk-milling technology of Tomioka Silk Mill clearly had an impact on the silk-milling industry throughout Japan.” (from Tomioka Seishijo Shoki Keiei no Shoso [“Aspects of Management During the Early Period of Tomioka Silk Mill”])

In addition to the impact within Japan, the raw silk produced by the women who worked at Tomioka Silk Mill was exported to the West, and enhanced the appellation of “Tomioka Silk.” Japanese raw silk played a role in building Japan’s international standing. The thread reeled by “the dexterous and delicate fingers of the factory girls” connected Japan and the world.

◀ The power of people lives on | The thread that pulled Japan into the modern world ▶